Mary Lou Williams in the Bebop Years

A dive into her 1940s recordings—and how they reframed what I thought I knew about bebop.

Viewers of the Jazz Bums know that I’ve been spending a lot of time with bebop lately. It started with a moment I wasn’t expecting: I put on a Charlie Parker record—something I’d heard before—and suddenly it just hit different. I just heard it. Like, really heard it. The way he plays—those flurries, that clarity, the drive—it suddenly felt like I was hearing the whole shape of jazz all at once, and it was electrifying—and from there, I found myself drawn deeper into that scene. While my listening habits are pretty broad, there's something about bebop that keeps pulling me back in. I’ve been spending time with the music of Charlie Parker, of course, but also Fats Navarro and Howard McGhee (t); Bud Powell and Al Haig (p); Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray (ts); Leo Parker (bs); Charlie Christian (g); Tadd Dameron (arr); and the rhythm section brilliance of Max Roach (d), Kenny Clarke (d), and Curley Russell (b). The more I listen, the more it opens up.

But despite all that listening, I recently realized there were still some huge names I hadn’t truly spent time with. Mary Lou Williams was one of them.

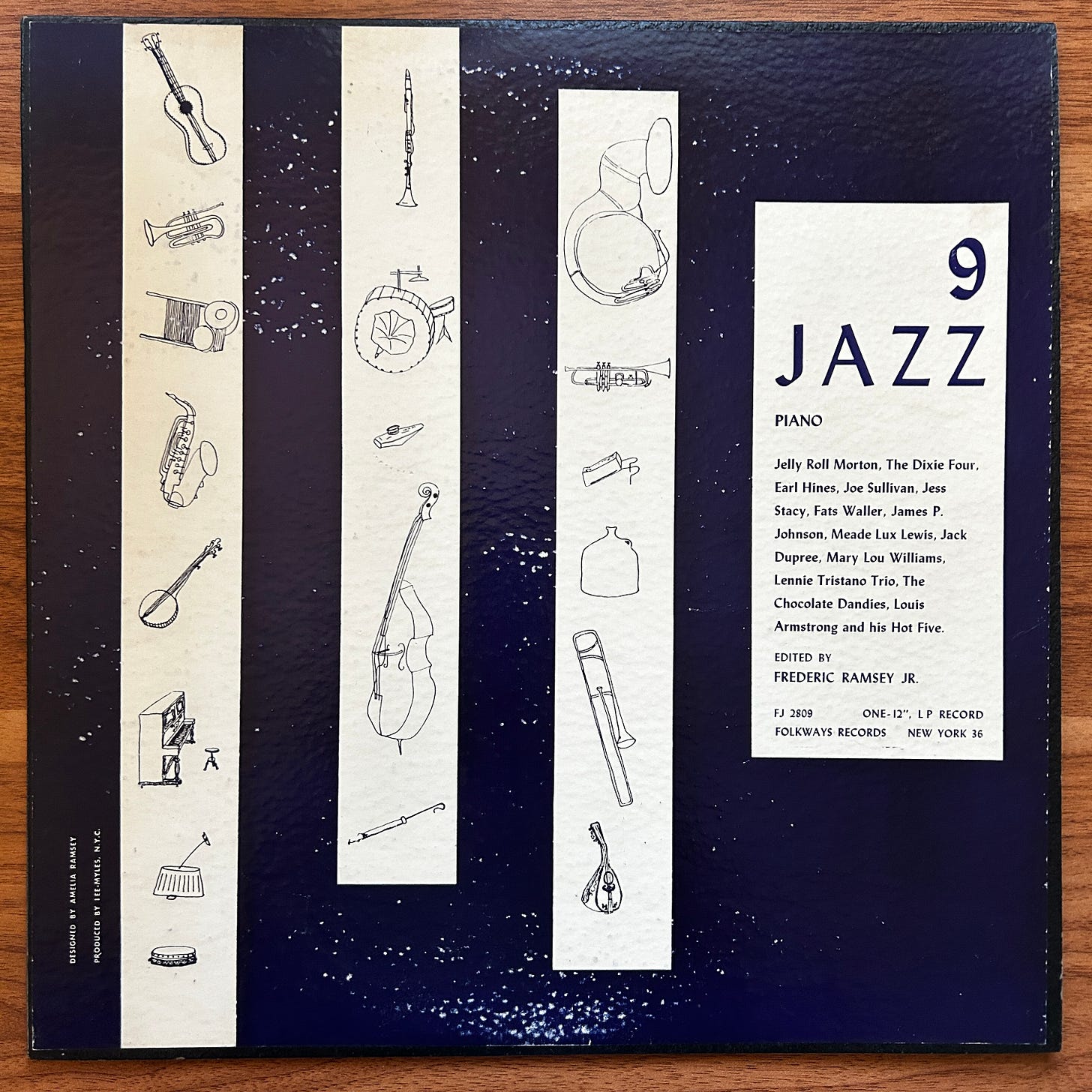

I was flipping through this old Folkways compilation LP—Jazz Vol. 9: Piano—and saw her name: Mary Lou Williams. It was sandwiched between some familiar piano players, but something about it jumped out at me. Her track on that record, "Libra" from the Zodiac Suite, stood out to me immediately. Side note, I made a video recently about that Folkways jazz series—a project that's really opened up a lot of early and foundational jazz recordings for me. Check it out here.

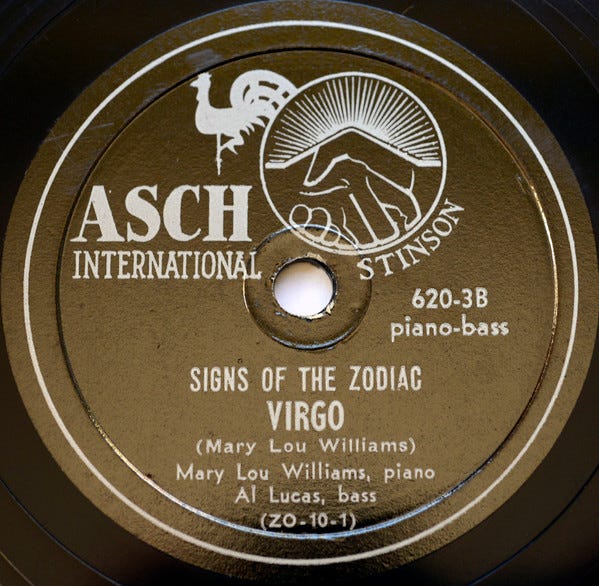

Hearing "Libra" sent me online to start streaming more of her work. That's when I found "Virgo," and everything changed. From the opening strains of "Aries," I could tell this wasn’t going to be just another piano record. It had a feel to it—loose, strange, fully alive—that pulled me right in. But it was "Virgo" that stopped me cold. It sounded like Monk. I mean, really like Monk—those playful dissonances, the rhythmic freedom, the space between notes. Except this was recorded in 1945. Monk hadn’t even released a record under his own name yet.

At the Center of It

That’s when I found this NPR piece about her Harlem apartment. Suddenly it all started to come into focus.

Williams wasn’t just a brilliant pianist or composer—she was there, fully embedded in the early 1940s Harlem scene. I learned she’d already made her name with Andy Kirk’s band and had written for Ellington. But instead of staying in that lane, she gravitated toward the new thing bubbling up at clubs like Minton’s and Monroe’s. After her gigs at Café Society, she’d head uptown to hear what Monk, Kenny Clarke, and Dizzy were working on (NPR).

And more than just showing up, she opened her home. Literally. Her apartment at 63 Hamilton Terrace became this unofficial hub. Bud Powell, Tadd Dameron, Kenny Dorham, Monk, Billy Strayhorn—they’d hang out, share ideas, write tunes. She kept a Baldwin upright in the living room. It sounds like a mix of jam session, workshop, therapy session, and crash pad. She called it a place where musicians could grow without ego.

That image really stuck with me—this Harlem apartment as a lab for modern jazz. I found a DownBeat photo from a 1947 in the Library of Congress archives that captures the vibe: Mary Lou, Dizzy, Tadd Dameron, Hank Jones, and others all gathered around her piano. It was taken by William P. Gottlieb, and it speaks to the kind of energy that room carried.

Seeing this photo made it even clearer—Mary Lou was right in the middle of it, helping to shape the sound and direction of modern jazz as it was being invented. Dizzy once said she was “always in the vanguard of harmony” (JSTOR). She defended Monk when critics didn’t get him. In her Melody Maker memoirs from 1954, she made it plain: “I have always upheld and had faith in the boppers, for they originated something” (Dave Ratcliffe Archive).

In her 1954 Melody Maker memoirs, she recalled the late-night sessions at Minton’s and Monroe’s—how secretive and intense they were. She said folks would scribble down riffs on napkins or shirt cuffs before they vanished. Bebop was still fragile, still forming. And she was in the room.

Her connection with Bud Powell especially resonated with me. She wasn’t just a mentor—she really looked out for him. Brought him food, helped him stay grounded. You can hear it in his playing too—that clarity, that structure in the chaos. Some of that comes from Mary Lou.

I’ve been spinning The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 recently, and knowing this history makes it hit harder. It’s not just Bud—it’s Mary Lou, Monk, all these influences moving through him.

The Other Asch Sessions

Now back to her music. After Zodiac Suite, I moved to her other recordings from the mid-’40s, also recorded by Moe Asch.

Her version of “Lady Be Good” especially—it’s swinging, yeah, but there’s something looser about it. Her phrasing is sharp and quick, with unexpected turns that catch you off guard. It reminded me of those early Jazz at the Philharmonic records: the speed, the spontaneity, the sense that something was cracking open.

There’s a modern edge to these mid-’40s recordings that doesn’t feel like a coincidence—it feels like a pivot.

Collector’s Corner

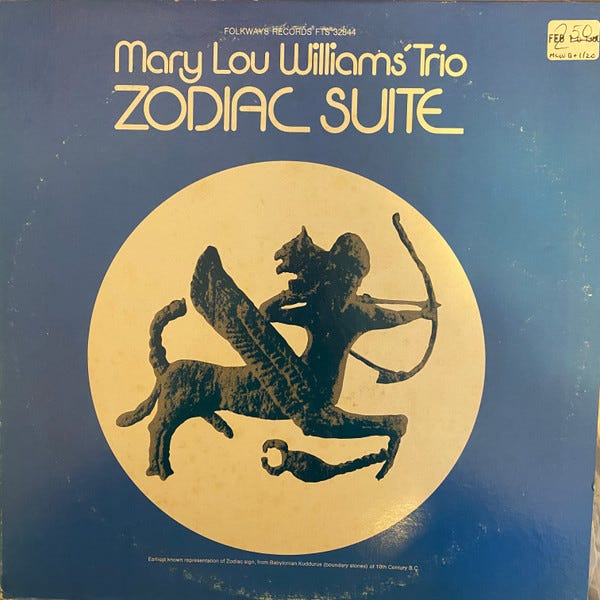

One thing I noticed while digging into her music: a lot of her mid-’40s recordings weren’t easy to find. Pieces like the Zodiac Suite and her other Moe Asch sessions were originally released on 78 RPM shellac—a format that made sense then but didn’t carry forward easily into later generations of listeners.

If you’re looking to track them down today, there are two key Folkways reissues to know about. The earliest LP release of Zodiac Suite came out in 1975 (Mary Lou Williams Trio – Zodiac Suite, Folkways FTS 32844). Original copies are pretty scarce and tend to run around $100 or more.

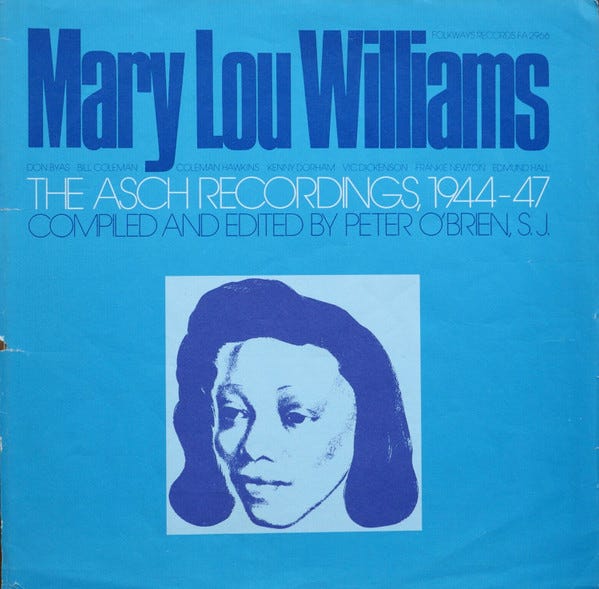

And then in 1977, Folkways put out Mary Lou Williams – The Asch Recordings 1944–47 (FA 2966), a 2xLP box set that pulls from across her mid-’40s sessions. It’s an incredible document of her shift from swing to something much freer, all captured as it was happening.

Final Thoughts

Getting to dive into the bebop years like this has been pure joy. Every record, every story just opens up more. I'm grateful to have the chance to chase this music—to listen, to learn, and to piece it together.

If you're falling down the same rabbit hole, I hope some of this helps. There’s so much to hear, and Mary Lou Williams is right there at the center of it.

Sources

NPR – A Woman’s Place: The Importance of Mary Lou Williams’ Harlem Apartment

https://www.npr.org/2019/09/12/758070439/a-womans-place-the-importance-of-mary-lou-williams-harlem-apartmentDave Ratcliffe Archive – Mary Lou Williams: My Life with the Kings of Jazz (Melody Maker, 1954)

https://daveratcliffepiano.com/MaryLouWilliams/MLW-MyLifewKoJ-1954.htmlJSTOR – “No Boundary Line to Art”: Bebop as Afro-Modernist Discourse

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/americanmusic.29.3.0332Library of Congress – Photo by William P. Gottlieb (1947)

https://www.loc.gov/item/2023868412Folkways Records Discography

Jazz Vol. 9: Piano (FP 71 / FJ 2809), 1953

Zodiac Suite (FTS 32844), 1975

The Asch Recordings 1944–47 (FA 2966), 1977Asch Recordings 78 RPM Releases

Signs of the Zodiac, Volume One (A 620), 1946

Carcinoma / Lady Be Good (Asch 1007), 1945Smithsonian Folkways

https://folkways.si.edu/

Thanks for this. I like the two versions of Stardust she did with Byas, also for Asch. And there’s this from 1949 recorded for King Records (bw Oo-Bla-Dee).

https://archive.org/details/78_knowledge_mary-lou-williams-mary-lou-williams-m-l-williams-d-best-m-lowe-g-duv_gbia0161492b

Have Scorpio on loop since this morning. Thanks for the impetus