Rediscovering Cool: How the West Coast Avant-Garde Changed My Understanding of Cool Jazz

Uncovering the experimental spirit that transformed my view of cool jazz.

For a long time, my view of West Coast cool jazz was anchored in the obvious: Pacific Jazz, Contemporary Records, Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Shelly Manne, etc. I thought I had a pretty good handle on this scene, but recently, something surprising happened that completely reshaped my understanding.

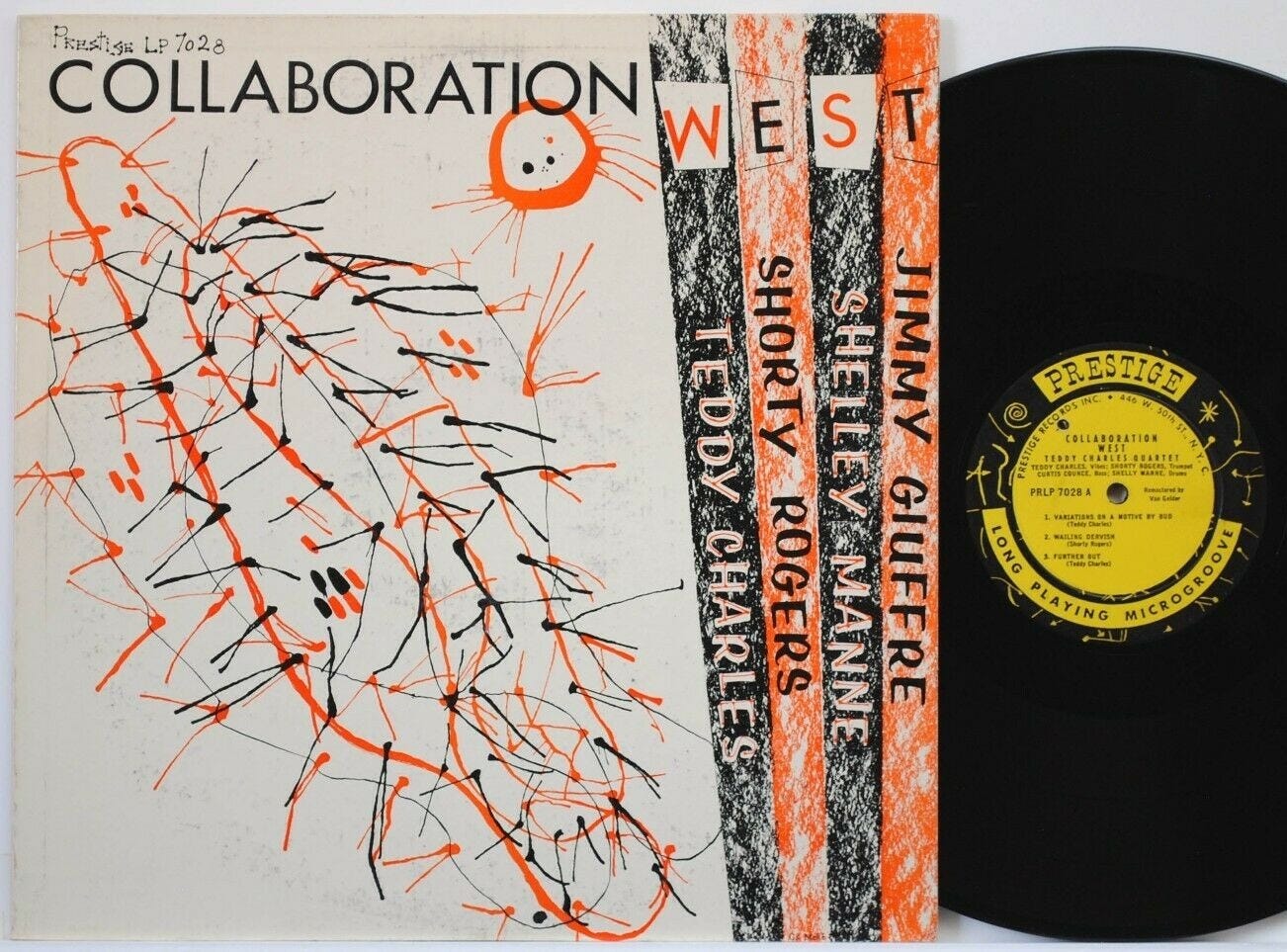

I was doing my usual rounds on eBay and Discogs, scanning saved searches, when a copy of Teddy Charles’s Collaboration West popped up for $40. I vaguely remembered sampling it before and thinking it sounded like a straightforward vibes-led record, nothing particularly earth-shattering. But this was a first pressing with the 50th Street NYC address on the Prestige fireworks label — the kind of early pressing I enjoy collecting, and which can often get expensive. So I started digging deeper.

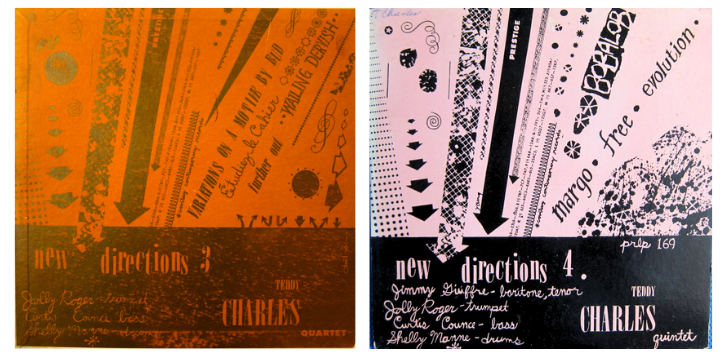

What I discovered was that Collaboration West pulls material originally released on 10-inch records: specifically, Teddy Charles New Directions Vol. 3 (recorded 1952) and half of Vol. 4 (recorded 1953). That immediately piqued my interest, especially when I saw that the Vol. 4 tracks included Jimmy Giuffre, a player I’d already developed a growing appreciation for, alongside Shorty Rogers on trumpet. I pulled up those tracks, curious, and was immediately struck: this was edgy, exploratory, with the kind of avant-garde spirit I knew Giuffre championed.

Even the track titles told the story: Vol. 3 gives us names like “Variations on a Motive by Bud,” “Wailing Dervish,” “Further Out,” and “Etudier le Cahier,” signaling a deliberate stretch beyond standard forms. Vol. 4 offers “Free,” “Evolution,” “Margo,” and “Bobalob,” titles that point toward motion, change, freedom. You can see that these players were aiming for something more experimental, more forward-thinking.

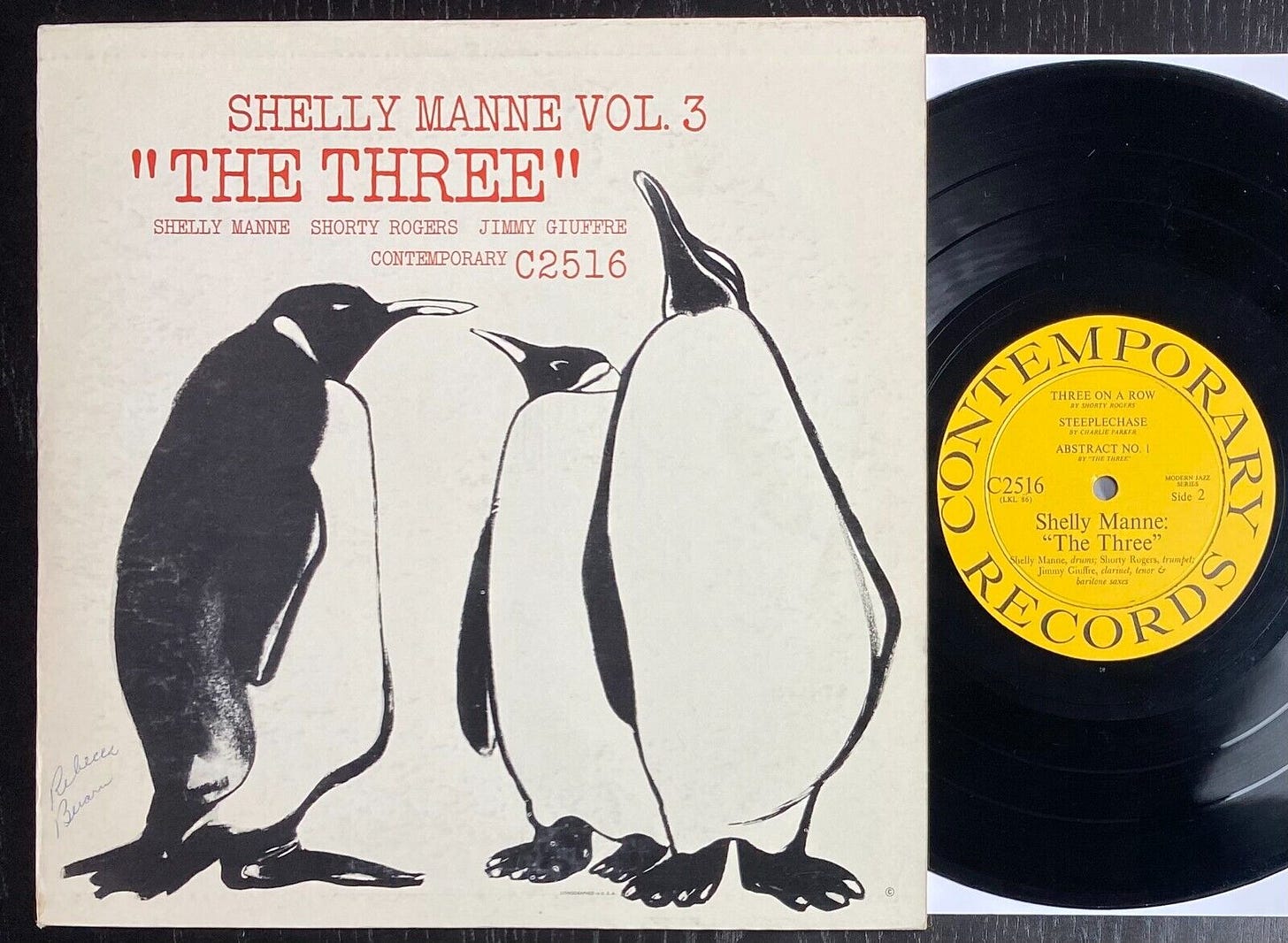

At this point, something clicked in my head, because a few months earlier, I had come across Shelly Manne’s The Three (recorded 1954), a trio session also featuring Shorty Rogers and Jimmy Giuffre. At the time, I was surprised by how avant-garde and stripped-down it felt, much more daring than the polished West Coast sound I’d grown used to. Now, hearing the New Directions Vol. 4 material, I realized I was uncovering a larger pattern: these West Coast players weren’t just delivering cool jazz polish, they were actively experimenting, stretching, and reshaping the music in ways I hadn’t fully appreciated before. And importantly, they were doing this several years before major landmarks like Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959) would formally usher in the avant-garde era.

Naturally, I went back to check out the Vol. 3 material, which features Shorty Rogers but no Giuffre. I half-expected it to fall back into more traditional West Coast cool territory, but no. These tracks, too, were pushing boundaries, playing with asymmetry, unconventional forms, and group interplay that felt ahead of its time. That’s when I realized I’d been missing something crucial: Teddy Charles, through these New Directions sessions, was experimenting in the early 1950s and connecting into a larger avant-garde thread running through the cool jazz scene.

The Importance of the New Directions Series

The New Directions series was an attempt to expand what cool jazz could be. Recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack studio and released on Prestige, these sessions brought together musicians from both coasts, creating a space where experimentation flourished. And here’s where another layer of realization hit me: for a long time, I’d mentally boxed 1950’s Prestige as mainly a hard bop label, but as I’ve been going back and collecting their early 10" records, I’ve started to see how much of that early material, with Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, Lennie Tristano, and even early Miles, is an extension of the Birth of the Cool aesthetic.

Listening to New Directions Vol. 3 and 4, you hear cool jazz becoming something more elastic, more abstract, more daring. You hear a young Jimmy Giuffre crafting the kind of ideas that would later define his chamber jazz work. You hear Shorty Rogers stepping beyond big-band charts into freer, more exploratory settings. And you hear Teddy Charles as a leader and conceptualist, testing the boundaries of what cool jazz could encompass.

A Changing Perception

What this discovery has taught me is that my understanding of cool jazz had been shaped by what was easiest to access, the familiar names and the most reissued titles, but a whole layer of experimental work was waiting once I started digging deeper. Discovering the New Directions sessions and connecting them to other avant-leaning projects like Manne’s The Three has opened up a new dimension of cool jazz for me and has given me a new perspective on what those West Coast players were up to in the early ’50s. Oh, and yes, I negotiated that Collaboration West copy down to $35 and ordered it.

Sources

Gioia, Ted. West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California, 1945–1960. Oxford University Press, 1992.

Hamilton, Andy. Lee Konitz: Conversations on the Improviser’s Art. University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Jost, Ekkehard. Free Jazz. Da Capo Press, 1994.

Kernfeld, Barry. The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Macmillan, 1988.

Lewis, George E. A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Milkowski, Bill. Swing It! An Annotated History of Cool Jazz. Billboard Books, 1998.

Ramsey, Doug. Jazz Matters: Reflections on the Music and Some of its Makers. University of Arkansas Press, 1989.

Schuller, Gunther. The History of Jazz, Volume 2: The Swing Era. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Spellman, A.B. Four Lives in the Bebop Business. Limelight Editions, 1985.

Tumpak, John. When Swing Was the Thing: Personality Profiles of the Big Band Era. Marquette University Press, 2008.

Yanow, Scott. Cool Jazz. Backbeat Books, 2004.

Yanow, Scott. Jazz on Record: The First Sixty Years. Backbeat Books, 2003.